RESTORE FAMILY FOR A CHILD IN NEED!

Help children separated from family

ALL GOD’S CHILDREN INTERNATIONAL

What We Do

We relentlessly defend children separated from family. With your partnership, working through God’s restorative power, we help children unlock hope and find a safe path back to family.

Why It Matters

In each child’s eyes, we see the reflection of our Creator. Together, let’s build a world where every child is restored to family, free from trauma, and embraced by the love of Christ.

How You Help

You can stand up for a vulnerable child now by sending a donation or sponsoring a precious boy or girl. Your faithfulness will help a child today and transform generations to come!

Help your child feel safe, calm, and empowered!

Get your FREE guide—filled with game-changing regulation tips—now.

TDC Conference

Tickets are now on sale!

This life-changing conference will take place September 29–30, 2026, in Austin, Texas.

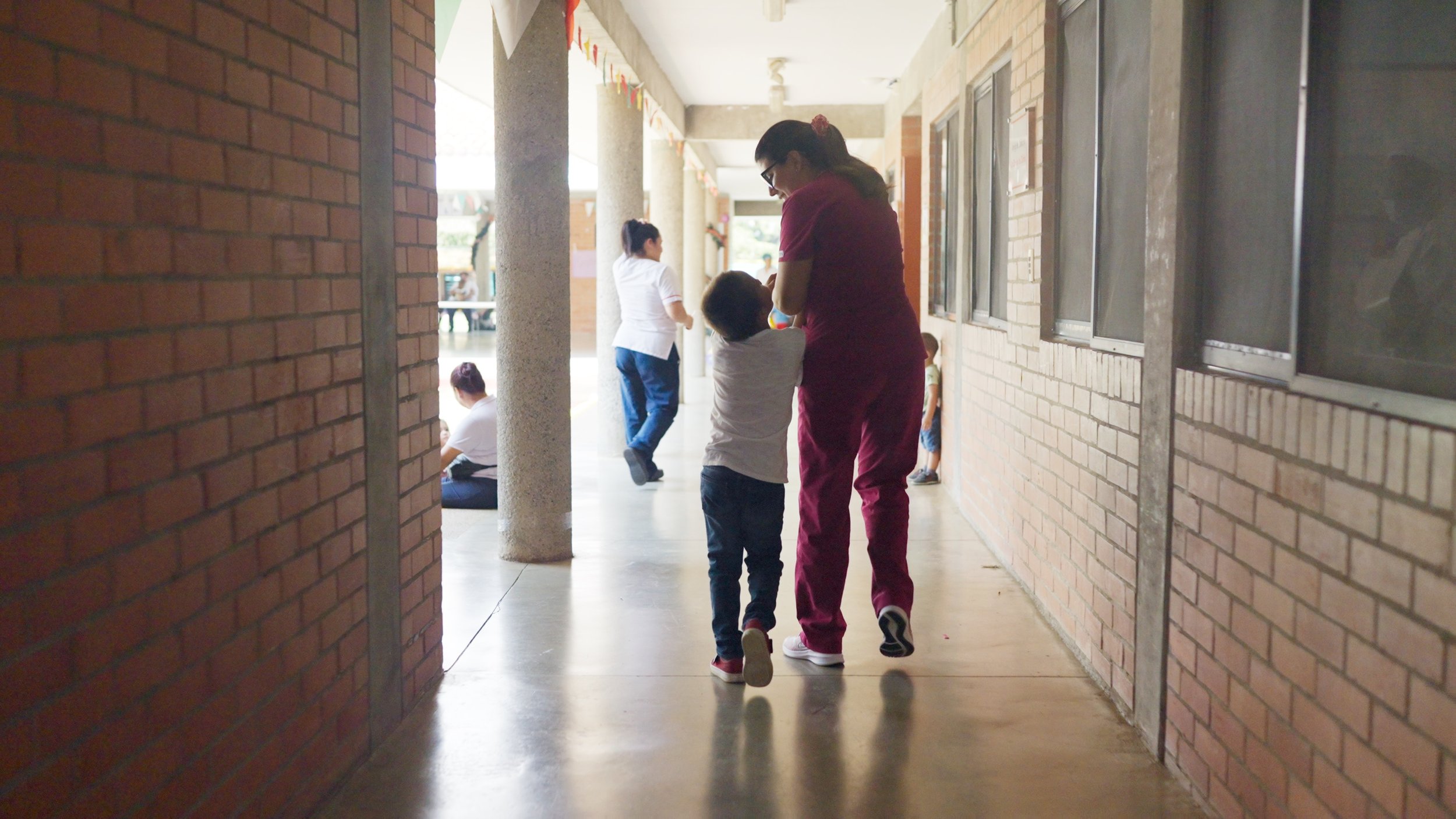

See What Restoring Families Looks Like on the Ground

Let’s disrupt trauma and be the hands and feet of Jesus.

After facing horrific trauma, all Aida could think about was running away. So she did.

Life on the streets was filled with danger, abuse, and loneliness. Her life felt completely hopeless.

But with God, all things are possible.

Discover how your gifts—and the miracle-working power of Jesus—help children like Aida find healing, restoration, and a safe path back to family. You can get involved and unlock healing by:

Help Rewrite a Child’s Future

Your generosity will bring hope and healing.

Right now, a child separated from family needs you. You’re invited to join All God’s Children International to relentlessly restore families and transform lives!

Whether a child is torn apart from family due to trafficking, child labor, or poverty, God can use you to help answer a child’s prayers. Together, we can reunite children with their parents or help children find a path to a safe, loving family. Because no child should be alone.

Through your generosity, children separated from family—who have endured unimaginable trauma—will receive vital care and find true healing. Our approach is both cutting-edge—based on the latest therapeutic research and timeless—rooted in God’s redemptive power.

Your Partnership Brings Hope Across the Globe

Throughout the last 30+ years, All God’s Children International has empowered children and families in 25+ countries and are actively standing up for children across Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, Europe, and the Pacific Islands.

Explore our work in…

Stories of Unlocked

Possibilities

Be inspired by children who found the strength to overcome.